Once upon a time in the 1920’s, a Prince and Princess living a fairy tale life with a fairytale endless amount of money, built themselves a house. Not just any house, of course. A fairy tale demands something very special!

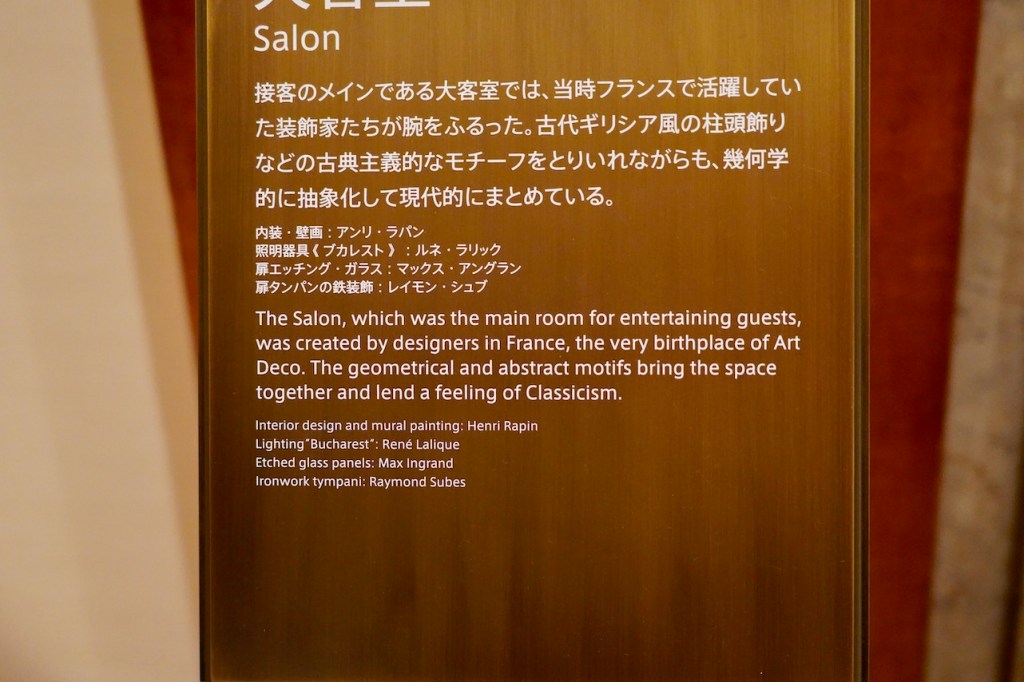

Theirs was an exquisite Art Deco mansion – with input from some of the world’s most famous architects and artisans of the 1920’s and early ‘30’s. Today the home remains an outstanding example of Art Deco. Think France’s Henri Rabin, Rene Lalique, Max Ingrand and Raymond Subes. They all contributed substantial work to this exquisite home. Marry their talents with the finest designers and craftsman of the age in Japan, and the result is an art deco treasure trove.

The home – now under the guise of an Art Museum – is open to the public in a place you probably wouldn’t expect – central Tokyo! All the more remarkable because the house miraculously survived the 1945 WW2 bombings that decimated most of Tokyo. The risk was very real, with bomb shelters built within the home’s extensive gardens – if you look closely you can still see the humps where they have been covered over.

The house was built for the Imperial Highness Princess Nobuko Fumi, a daughter of Japanese Emperor Meiji, and her husband Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, a leading royal himself as head of the Asoka branch of the Imperial family. Married in the spring of 1909, Prince and Princess were a very modern couple with an international outlook, travelling through Europe, the UK and the United States, and developing a particular love for France where they lived together for two years.

The gardens – both European style and Japanese – surround their home and, like the house, are much the same as when they were first designed – providing a quiet and restful oasis in the city. The Prince liked to cultivate plants, and when the house was being built, he instructed that ancient trees on the property be preserved as much as possible. One tree, estimated to be 300 years old at the time, was carefully uprooted and successfully replanted about 160 meters away.

The property was taken over by the Government after WW2, and is now home to the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum. The house and gardens cover more than 7 hectares, and are open to the public – be prepared for a special art deco treat and an enjoyable garden stroll.

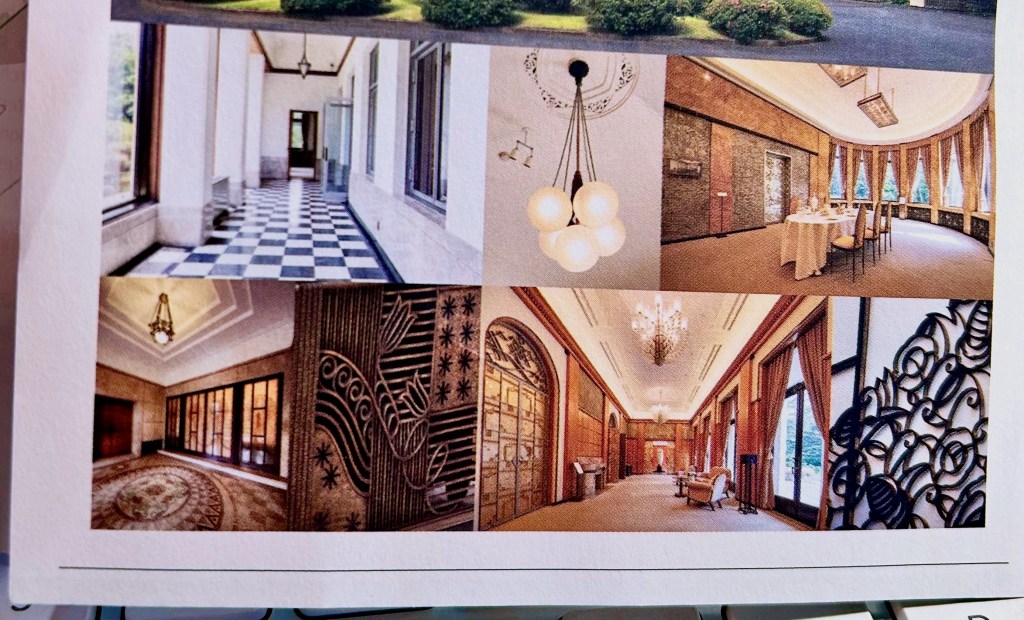

From the property’s front entry, you approach the house by walking along a long tree lined avenue. The exterior of the house impressed me as quite discreet for what was an imperial household, but everything inside took my breath away.

The main entrance provides a hint of what’s to come with glass-relief doors by the French glass artist René Lalique. It was a new design created especially for the Prince Asaka Residence and executed in pressed glass, each door features a standing female figure surrounded by a backdrop of open wings.

The mosaic floor was created from natural stones, and designed by Takashi Oga of the Imperial Household Ministry’s Construction Bureau.

The ground floor, meant mainly for entertaining, is the showcase, while upstairs was the family’s private domain and, though still stylish, is more subdued. Every room you enter in the double storied home contains meticulously crafted art deco treasures – from doors, fireplaces, hand tiled mosaic floors and curved marbled walls to artistic light fittings, chandeliers and paintings. And so much more! Some have since been mass produced, but in this house they are the originals. That they are together in the one home is almost beyond imagination.

Teien hosts various art exhibitions – a German design exhibition was on when I visited in May this year (2025). But it is the house that’s the show stopper. I wonder if many Tokyo visitors miss seeing it because it’s billed an Art Museum? On our visit in May, we saw only two other westerners.

I have been to Tokyo many times over the past few decades, and for me, this Art Deco house and its beautiful gardens are one of the most outstanding features of the city!

Princess Nobuko Fumi and Prince Yasuhiko Asaka were both young when they married – she 18 and he in his early twenties. They were a good looking couple and appeared to be a good match. He looked handsome, but his face became pinched with age, and the addition of a tiny moustache in later years did nothing for his fading looks. Almost every photo I’ve seen of the Princess shows her dressed fashionably in western style. She looks an accomplished woman, capable and dependable – someone who might be a good friend. The couple would go on to have four children together – two Princes and two Princesses.

I can’t include photos of the couple and their family because of copyright. But you can find plenty on Getty Images and other Internet sources.

By 1922, the Prince had graduated from the Japanese Imperial Army Academy as a Lieutenant Colonel and was sent to France for further military studies. Tragedy struck when he was critically injured in a car accident. The driver, his cousin, was killed. Princess Fumi rushed to France to care for her husband, and they stayed on together for his lengthy rehabilitation. The stay was pivotable for their eventual house building project back in Tokyo, with the couple becoming passionate about the Art Deco style and making important connections with some of France’s finest and most famous craftspeople of the time.

The Princess had an artistic soul. She painted plants in watercolors under the instruction of French artist Ivan-Léon-Alexandre Blanchot, who later contributed some stunning work for the Tokyo house. On the request of the Princess, Blanchot produced an impressive marble relief in the Great Hall, entitled Children Playing, and a floral relief on the wall of the Great Dining Room. His “BLANCHOT” signature can be seen on both. The Dining room relief was originally made of concrete, but it was damaged in transit from France. It was meticulously remade in Japan from plaster.

In 1925, Blanchot also produced a stunning bronze statue of the Princess that shows her with a stylish bob hairstyle, a 1920’s dress, a strand of pearls and a coat hung casually over one shoulder. To me, it shows a slim and elegant Princess who was suited to the latest French fashions and who was unrestricted by Japanese Imperial modes of dress. The statue remains in the Teien museum collection, and you can see a photo of it online at the Gallery’s website, along with photos and paintings of her.

The famous Japanese architect Gondō Yōkichi worked with the Imperial Household Ministry’s Construction Bureau, and played a key role in designing the house. He had studied modern architectural styles and designs in Europe and America in the mid 1920’s, including Art Deco in Paris.

The building is often referred to as the Prince’s house – but it was the Princess who collaborated closely with the French and Japanese designers and artisans to ensure it was very much her home. From the start she was very involved in the details to ensure her own artistic stamp on the project.

Work began in 1929, but the fairy tale would take a tragic turn. Princess Fumi died of kidney disease within a year of the house’s completion in 1933. She was only 42. Only a year before she was photographed playing golf, looking healthy and robust, so the illness may have been quite sudden.

The family continued to live in the house for many years before being turfed out after World War 11, with the home seized by the State.

The house definitely retains a family feel, even now in its presentation as an Art Museum. I’ve been in other royal properties in Japan and in Europe, but I felt none had the homely feel about them that this one does. Again, quite an achievement to create such an exquisite house that still feels like a regular family home.

Perhaps Princess Fumi’s early demise was for the best because her husband would bring international disrepute for her family. The Prince was sent to China in the second Sino-Japanese war, rising to the rank of an Army General. While there, he acted as the temporary campaign Commander, filling in for General Matsui who was ill with TB. It’s claimed that as Acting Commander he issued the order to kill all captives. This led to the infamous Nanjing Massacre or Rape of Nanjing – one of the worst wartime atrocities in history. It’s still debated whether he personally issued the actual order, but he didn’t stop it. Neither did Matsui on his return to Command. Matsui would be subsequently executed after WW2 for failing to halt the massacre.

The Prince also served on Japan’s Supreme War Council throughout WW2. He was interrogated by the Allies at the end of the War, but did not face court. His close position as a cousin to the Emperor and the widower of the previous Emperor’s daughter may have saved him.

America’s General Douglas MacArthur granted immunity to the Imperial Family, though like many Japanese Royals, Asaka and his three remaining children lost their Royal Status and privileges and became commoners. One son, Prince Asaka Tadahiko had renounced membership in the Imperial family back in 1936, and was created Marquis Otowa. This must have been highly unusual and seems to have disappeared in history, as everything I research says no Japanese royals renounced their title in the 1930’s. I can’t find out any information as to why he took this action. During WW2, he served in the Japanese Navy and was killed in action in the Pacific during the Battle of Kwajalein.

Prince Asaka clearly retained wealth after the War, retreating to the family summer villa Atami on the idyllic Izu Peninsula where he lived a long and privileged life until his death in his early 90’s. I haven’t been able to find anything about the villa, but it would have been a substantial property. There is one entry on the Internet suggesting it is now open to the public, but the photo attached to the article is of a villa built for a German. So I think that’s a mix up. I’ve also read that the villa is now a hotel, but my searches haven’t substantiated that.

The former Prince continued his passion for golf after leaving Tokyo and took a keen interest in golf course design. In the 1950s, he was the architect of the Plateau Golf Course at the Dai-Hakone Country Club, now managed by the Seibu Prince Hotels and Resorts – no connection with Prince Yasuhiko Asaka that I can detect. He also became a Roman Catholic, an event that made news in the New York Times.

Before going to see Teien, I understood it was forbidden to take photos within the house. But that isn’t so. You can’t take photographs of any rooms featuring an exhibition. But you can photograph most of the rest of the interiors and the gardens. I wish I had realised this as I progressed through the house, taking quick little snaps!

The house and gardens remain much as they were originally – including a large lawn area now open to the public and ideal for picnics.

Ensure that you walk to the Japanese garden section where you will find the Kouka Teahouse designed by a Tea Master and built by a Master Osaka carpenter. Sadly, the Princess never saw the tea house as the Prince had it built in 1936, long after her death.

I was standing in the tea house during my Spring visit when I looked out onto a path leading up through the Japanese gardens, and spotted a young woman admiring plants there. I quickly took a photo, imagining one of the young Princesses wandering through the garden, enjoying it.

The Teien Art Museum doesn’t deny the connection with Prince Yasuhiko Asaka. He and the Princess are briefly mentioned in the Art Museum brochure you receive on entry. But there’s no photos in the brochure of the couple or their family in the brochure. That, to me, says a lot. The connection is kept low key, skimming over the family’s loss of the home and Imperial status and the dark wartime history associated with the Prince.

I can understand this in relation to the Prince, but I wonder if the Princess should be given a higher profile at the Art Museum, given her artistic input and contribution to the house. She had been in her grave four years before the Rape of Nangkin. In these modern times, should a long dead wife be held responsible or even connected to her husband’s behaviour and alleged crimes in the years after her death?

The Museum does have many of the family’s possessions, personal photographs and momentos in its collection. And I wish more of those pieces, particularly items associated with the Princess and the children, had been displayed prominently at the house.

After World War 11, the home was used for seven years by former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida. For another nineteen years, it served as a State Guest House.

Finally, it opened as the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum in 1983, and it is now recognised as a National Important Cultural Property due to its well-preserved original and magnificent Art Deco features.

There is an entry fee. It’s well worth it! By the entrance is an upmarket restaurant and a museum shop that you can access without the entry fee. I enjoyed lunch in a classy little cafe in a modern extension to the main house where I enjoyed an excellent curry and a matcha (green tea) tiramasu – so good! The cafe adjoins another museum shop that is well worth browsing.

Teien doesn’t feel like an art museum. More like a highly elegant home that is hosting an exhibition. For me, it is a place not to be missed when visiting Tokyo!

ACCESS: 7 minutes walk from the Meguro Station on Tokyo’s circular JR Yamanote Line (East Exit) or the Tokyo Meguro Meguro Line (main gate). It is about a 20 minute train ride from Tokyo Station to Meguro Station. Check the Museum website for opening times, admission fees, and facilities for visitors.

IF YOU ENJOYED MY STORY, PLEASE LEAVE A LIKE – OR EVEN A COMMENT – TO ENCOURAGE ME!